I presented this paper to the Centre for Critical Theory at University of Nottingham. Many thanks go to Andy Goffey for the invitation.

I’d like to open a conversation about animacy, matter, and the molecular status of twins, to question what it is that makes urgent the peculiar exigency of twins, the sense that they are both with ‘us’ and against ‘us,’ and so throwing doubt over what sort of ‘us’ is being claimed and where that relation is being located. I would be truly grateful for any comments or recommendations you might have, anything that you feel seems important or germane, but equally, I’d like to invite an intellectual mercy killing if you think that I’m going seriously off the rails.

In what follows I’d like to provide a commentary on Mel Chen’s work on ‘animacies’, a concept that relates to, describes, and can help challenge hierarchies of agency, awareness, mobility, and liveness, to patrol the distinction between what is ‘alive’ and ‘dead.’ Chen argues a scale of animacy has supported normative concepts of ‘the human’ since, at least, Aristotle’s De Anima, and continues to regulate “gradations of lifeliness”[1] from inanimate, ‘dead things’ – minerals, stones and other non-sentient objects – constitute a zero-degree of agency – through to vegetables, smaller insects and non-vertebrates, to larger animals, mammals, children, women, and finally Man as a maximally agentive figure. Animacy stratifies Nature according to liveness, purpose, and sentience over which humans assume privileged access.

For Chen, understanding the racialised, sexualised and abelised political ecologies that can feed off and maintain the animacy scale helps to “trouble the binary of life and nonlife [to give a clearer] way to conceive of relationality and intersubjective exchange”.[2] The failures, breaks, and contradictions between the animate and inanimate reveal how the scale of animacy “must continually interanimate in spite of its apparent fixedness”[3] – hence, her book is called ‘animacies’ on the understanding that other practices, epistemologies, and ontologies are possible.

Ok, so how do twins fit in? And this, perhaps, is my main point, fittedness doesn’t quite cover the specific and often contradictory forms of mobility that twins achieve along this unstable cline, a mobility that is neither ‘culturally’ or ‘naturally’ directed, but articulates itself through the numerous ways that twin bodies can, do, and might matter.

There are a number of ways that twins may interanimate across and along the animacy hierarchy – from a sense of incongruent codependence, to adult infantalisation, to the ableist logic of extrasensory communication to the dis-ableism of infant language impairment. But I’ll focus the rest of this paper on the use of twins in the natural sciences, especially in psychology, genetics, and epidemiology, where they are thought of and make explicit ‘things’; people whose agentive powers both plunge down the animacy scale through their instrumentalisation as and proximity to laboratory materials, animals, and tools – ‘the non-human’ – and projected up the animacy scale, for being a powerful investigatory community generating, to quote one twin researcher “unique insights […] simply by acting naturally”[4]. Their every life event, decision is resonant with scientifically universal information – their bodies are used to stabilise and articulate new vital locations, processes, and therapeutic possibilities.. This is “knowledge and insight for everyone,” to quote one leading epidemiologist, “not just for twins”[5] It’s this particular animation of twins that I’d like to focus on for the rest of this paper and I hope to have time later to consider whether there’s a materialism of twinship that permits us to look at relations and intersubjective exchange in a different light.

***

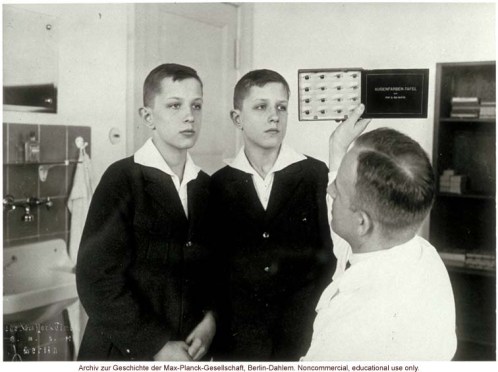

So: twin things. Those born together in a single gestation first entered studies of heredity, genetics, and then a wide range of allied fields and subfields, through Galton’s biometric analysis of “nature and nurture”– a phrase first coined in relation to his twin studies of the mid 1870s. Guided by depth biology Galton hoped to discover the mechanisms that allowed twins to “keep[…] time like two watches, hardly to be thrown out of accord except for some physical jar”[6] From Galton we can trace the long process that has scientifically en-thinged twins – recruited them as evidence and material, imagined and treated as tools in order to animate new theories of life, development, and disease. Over 1.5 million twins and family members now participate in research worldwide, measured for a huge variety of physical and behavioural traits.

Chen, whose academic background is in comparative linguistics, argues that “language users use animacy hierarchies to manipulate, affirm, and shift the ontologies that matter the world”.[7] With this in mind, consider the status of twins when researchers like Nancy Segal refer to her research participants as “a powerful investigatory tool”[8] or as “living laboratories”[9] Twins matter, but particularly as they serve as efficient, exploratory and contingent tools. Robert Plomin describes his studies of identical twins who differ for a given phenotype as “a sharp scalpel for dissecting non-shared environmental effects from genetic effects.”[10] Twins are ‘technical things’ absorbed into experimental systems and used to bring to light and make matter the epistemic objects that comprise molecular processes.[11] Returning to the animacy scale, I think this use of twins problematizes both the inanimate, stone-like inertia of ‘the thing’ and the spatial and temporal integrity of its all-powerful human antagonist. However, I’m not sure that Chen’s work gives satisfactory guidance when she argues that “when humans are blended with objects along this cline, they are effectively ‘dehumanized’ and simultaneously de-subjectified and objectified”.[12] She uses a distinction between object and subject that finds sustenance in Martha Nussbaum’s claim that objectification occurs whenever “one is treating as an object what is really not an object, what is, in fact, a human being.”[13] Twins, however, are not only treated as or “blended” with things, but are experimental bodies understood as a complex assemblage of cell lines, gene expression levels, methylation sites, and microbial communities, to name just a few kinds of ‘matter’ that twin research has tried to articulate. Somehow, twins remain human twins, realised in and through and perhaps despite their thingliness.

It’s for this reason that I find Chen’s animacy scale or cline both incredibly useful but also rather linear, her discursive approach too narrow for the range of practices that I take to doubly en-thing twins – practices that not only render them technical objects in contemporary genomic research – beings that are measured, sampled, computed, and ‘shared’ as part of a globally-configured experimental apparatus – but also providing the evidence for what Nikolas Rose has characterized as the “molecularization of vitality”; which, with and among other things, decomposes, anatomizes, manipulates, amplifies, and reproduces “tissues, proteins, molecules, and drugs […] to be regarded, in many respects, as manipulable and transferable elements or units, which can be delocalized – moved from place to place, from organism to organism, from disease to disease, from person to person.”[14]

Here the role of animacy forces a set of ethical, epistemological, and ontological decisions that, for me, makes a critical medical humanities approach to twins necessary and possible – should twins be defended against instrumentality, safeguarding an autonomous, lively, unique, unbreakable and free ‘human’, or, can we break with the scales of anthropocentric privilege since, doing so, pursues the more difficult and critical – as in urgent or decisive – and certainly more risky task of understanding how and why twins come to matter in different ways and at different times.

***

If animating twins permits a recalibration of what it means to instrumentalise bodies conceived at a molecular scale, then I join those who are keen to challenge the strict partition between a human inner and non-human outer – to perforate “the exclusionary zone made of the perceptual operands of phenomenology”[15], and, by dismissing its correlationist accessory, which thrives through a plural multiculturism set against a static mononaturalism, I take the study of twin animacies to open up different, transcorporeal, transobjective socialities. Mel Chen’s characterisation of molecular intimacy is, I think, somewhat problematic, based as it is on physical absorption and assimilation: “When physically co-present with others, I ingest them. There is nothing fanciful about this. I am ingesting their exhaled air, their sloughed skin, and the skin of tables, chairs, and carpet of our shared room”.[16] I am both wary of the notion of physical co-presence being valorised and relied on here but also of how Chen’s human-nonhuman assemblies bare some similarity to Jane Bennett’s attempts to elevate “the shared materiality of all things”[17] to stress how each human is “a heterogeneous compound of wonderfully vibrant, dangerously vibrant, matter.”[18]As in Chen’s analysis, this vital materiality finds its force in accommodating and absorbing what is foreign. Bennett writes: “Vital materiality better captures an ‘alien’ quality of our own flesh, and in so doing reminds humans of the very radical character of the (fractious) kinship between the human and the nonhuman. My ‘own’ body is material, and yet this vital materiality is not fully or exclusively human. My flesh is populated and constituted by different swarms of foreigners”[19] We might characterize some of this object-oriented thinking as operating under what Chen calls the “xenobiotic”[20] where the argumentative thrust of these new ontologies, which borrow so much from molecular biology, follow particular trajectories of inclusion as they extend agency into the world by locating the nonhuman within.

***

To revive Chen’s description of the animacy scale and apply it to her own interanimations, I want to ask in what way does focusing on particular kinds of vibrant things “manipulate, affirm, and shift the ontologies that matter the world”? What, after so many years of humanistic, anti-essentialist broadsides against molecular biology, are we to make of the genetic matter that co-ordinates the somatic identity of twins in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? Because, if there is one question same-sex twins are asked by strangers it is this: identical or non-identical, monozygotic or dizygotic? This is gene talk through and through and it’s how twin bodies matter between molar and molecular scales. Despite the informatic metaphors of gene action – where ‘codes’ and ‘scripts’ are ‘read’ and ‘translated’ – Barry Barnes and John Dupré remind us that “DNA is stuff, and we are able to relate directly to it and gain knowledge of it as such–where to find it, how to separate it off, how it behaves as material, and so forth […] DNA is indeed a tangible material substance.”[21] Through twins and the research in which they participate, that tangibility has been made possible. And its on this basis that, in my approach to twinning, I want to resist the absolute collapse of the inner and outer, the rather lava-lamp-like materialism of the xenobiotic, since one does not become a twin in the same way one becomes infected or toxic; twinship may share something in common with concepts of biosociality, biological or genetic citizenship, but not in the same way that all of these terms have become tied in the STS and sociology literature to the circulation of “disease, disfigurement or disability”[22], what we might think of as the ‘proper terrain’ of biopolitics. No, I think the animate matter of twins makes another perspective possible; one that does not let the molecular elide the molar and one that does not over- or undermine the physicality of genes, but one that opens up the thingliness of specific people whose animate identity is internally-external, materially distributed within and between bodies.

[1] Chen, Animacies: Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), p. 167.

[2] Chen, Animacies, p.11.

[3] Chen, Animacies, p.30

[4] Nancy Segal, ‘Twins: The Finest Natural Experiment’, Personality and Individual Differences 49 (2010), p. 317.

[5] Tim Spector, ‘The Use of Twins in Research’. BRC Biomedical Forum, Guy’s Hospital, 9th January 2013.

[6] Galton, ‘The History of Twins as a Criterion of Nature and Nurture’, p. 574

[7] Chen, Animacies, p. 42.

[8] Nancy L. Segal, Born Together–Reared Apart: The Landmark Minnesota Twin Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2012), p. 2.

[9] Nancy Segal, Entwined Lives: Twins and What They Tell Us About Human Behavior (New York: Putnam, 1999), p. 1.

[10] Robert Plomin, ‘Commentary: Why Are Children in the Same Family So Different? Non-Shared Environment Three Decades Later’,International Journal of Epidemiology 40 (2011), p. 587.

[11] For more on the distinction between ‘technical’ and ‘epistemic’ thing taken from Hans–Jorg Rheinberger, Towards a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube (Stanford: California University Press, 1997), pp. 28–29.

[12] Chen, Animacies, p. 40

[13] Martha Nussbaum, ‘Objectification’, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 24. 4 (1995), p.257

[14] Nikolas Rose, The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), p.13, p. 15.

[15] Chen, Animacies, p.209

[16] Ibid.

[17] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), p. 13.

[18] Bennett, Vibrant Matter, pp. 12–13.

[19] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, p. 112

[20] Chen, Animacies, p. 208.

[21] Barry Barnes and John Dupré, Genomes and What to Make of Them (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 2008), p. 64

[22] Rose, The Politics of Life Itself, p. 137.

(monozygotic) twin pairs to demonstrate the performed and negotiated quality of twin identities in a society largely organized by, and structured for, singleton expressions of self and sibling experience. With chapters organized around broad themes – ‘Twinscapes’, ‘Talk’, ‘Performance’, ‘Body’, ‘Bond’, ‘Culture’, and ‘Twindividuals’ – Davis weaves her own experience of being a twin and of attending conferences such as the

(monozygotic) twin pairs to demonstrate the performed and negotiated quality of twin identities in a society largely organized by, and structured for, singleton expressions of self and sibling experience. With chapters organized around broad themes – ‘Twinscapes’, ‘Talk’, ‘Performance’, ‘Body’, ‘Bond’, ‘Culture’, and ‘Twindividuals’ – Davis weaves her own experience of being a twin and of attending conferences such as the